1954, THE MICAELENSE YEAR

José-Louis Jacome, November 24, 2020

The Big Trip - Leg 1

For most of the 1950s Azorean pioneers, the boat trip they made to immigrate to Canada was also the first trip of their lives. At the time, even travel within São Miguel was rare and counted. It was very expensive and the rural workers financial means were very limited. Pioneer Afonso Maria Tavares wrote in his biography that many people born and died in the island without ever visiting Ponta Delgada, its capital, especially those living in the Nordeste area, 40 km away.

The one-way ticket to Canada cost 5,300 escudos, the savings of a lifetime. In fact, emigrants had to budget around 11,000 escudos for all travel expenses, a sum few of them had. Usually, they had to borrow to make their big trip. The first leg was done by ship until the mid 1950s; it lasted 5 days on average. Upon arrival in Halifax, immigrants had to take a train to Quebec, Montreal, Toronto and other Canadian cities. The trip from Halifax to Montreal lasted 2 days. While this 7-day trip doesn't compare to the 120-day boat trip to Hawaii, which several Azorean families took in the mid-19th century, it was a demanding trip nonetheless. A few decades earlier, many had also immigrated to the United States and Brazil on much less comfortable and slower ships than the Nea Hellas and the Homeland. My great aunts Marianna and Belmira, Manuel Jacome, my grandfather's brother José, his sister Maria dos Anjos and her husband Manuel Pereira, immigrated to the United States aboard the Roma, Romanic, Cretic and Canopic ships in the 1910s. The big trip was always a heartbreaking decision. For the vast majority, the return trip was not planned. In fact, few Azoreans returned to live in their country after emigrating.

Contrary to what one might think, although they inhabit isolated islands in the middle of the Atlantic, Azoreans have always feared the ocean. For them, it was a monster. Most could not swim, including fishermen. When they boarded a ship, Azoreans also confronted a devil they feared. This article traces the typical journey of an Azorean leaving São Miguel for Montreal in 1954, the trip my father and thousands of other Azoreans did in the 1950s. The ship portion of the trip follows.

Aboard The Homeland (São Miguel - Halifax)

The Azorean pioneers I have met speak little of the ship and life on board. They mostly talk about sea sickness and the ever-rough ocean. Few texts inform us of the 5 days spent aboard the Homeland. Even the articles written by the Azorean chroniclers who accompanied them tell us more about the ocean and the weather than what goes on inside the ship. Columnist João de Oliveira, who accompanied the first contingent that left on March 22, gives us some clues in his travel diary or Diário da Viagem which he published on April 4 and 6 in the Correio dos Açores newspaper. He provides some interesting clues in his March 25 diary notes describing the entertainment in the dining room. “That day the crew had decorated the room and provided colorful hats for everyone. The whole thing had an air of carnival. We drank unlimited champagne. To the sound of the orchestra, passengers danced late into the night. We returned to our quarters in the wee hours of the morning. »

During the second Homeland trip, two chroniclers accompanied the 450 Micaelenses; Manuel José Cordeira Martins de Candelária and Henrique da Costa Dutra of Ribeira Seca. Here again, we learn very little about what is happening on board. From the articles they published in the Diário dos Açores newspaper, Carlos Cordeira and Artur Madeira, two University of the Azores professors, wrote some rare details about life aboard the Homeland in their Portuguese Reviews, Vol .12, No. 2. My free translation follows.

“There was a religious service celebrated by an Italian Catholic priest. Azorean emigrants had two information sessions per day to prepare them for life in Canada.

The first class dining room on board the Drottningholm (Homeland). (thegreatoceanliners.com)

These sessions were presented by an inspector from the Junta da Emigração. They could attend movies and concerts offered by the Homeland Orchestra. Several activities were organized; the staff formed singing groups. The Azoreans sang several of their traditional cantigas ao desafio accompanied by guitars, violas and accordions. The ship was carrying Italians to Canada and the United States. Several Azoreans attended the dance evenings. They watched the Italians dance with beautiful Italians girls. Most Azoreans would have liked to imitate them but did not know how to dance like them. The meals were plentiful. Our compatriots ate with appetite, especially when the sea was calm. They didn't like Italian salads ..." (1)

The conditions of the trip were considered to be above average; the ship had a good standard following many improvements. The atmosphere and the many activities offered made life on board very pleasant. Several Azorean emigrants suffered from seasickness in one or other of the Homeland trips. I remind you that regardless of ocean conditions, Azoreans just hated it. There was another fact, the ship had a tendency to sway, a certain instability resulting from its design and construction in 1904. To close these lines on life aboard the Homeland, I am adding the very moving testimony of Gil Andrade, a Micaelense from São Roque; a small community close to Ponta Delgada. He tells us about his trip aboard the Homeland on April 23, 1954, my father was aboard.

Once its route Genoa-Naples-Halifax-New-York was completed, the Homeland returned to Europe. Several emigrants were able to write to their families. (1) My father sent a letter and the following postcard to my mother.

Audio Testimony* from Gil Andrade (in portuguese)

Now, after listening to this Gil Andrade testimony, I understand better the fish story my father told me several times, a story that always confused me. He often said that the weather was so bad during the trip that sometimes you could see the fish through the portholes of the ship. According to Gil Andrade, the 450 Azoreans were all placed in the lower floors. They were near the water level. When the ocean churned, the unstable ship was literally washed away by the waves. His nose sank into the ocean for long minutes. The Azoreans then

found themselves among the fish, under water. “It was terrible, I thought we were going to die, and that we would never see Canada.” says Gil Andrade. "Then the nose of the boat was lifting, it was going up and up, you could hear the loud thud of the engines, it was a terrible trip, I will never forget it. Finally, thank God, we arrived in Halifax as planned on April 29 after 5 days at sea.” says Gil Andrade.

A Ticket Costing a Life of Work

Today, many of us take the plane for a trip, sometimes for several trips a year. In the 1950s, only the very rich could think of a trip. With $1,000, you can get a return ticket to many places. We often look for the best prices, but compared to that time, tickets are quite cheap. The average Canadian will earn the ticket price within a week. Many will earn it in a few days. The situation was quite different for Azorean emigrants in the 1950s.

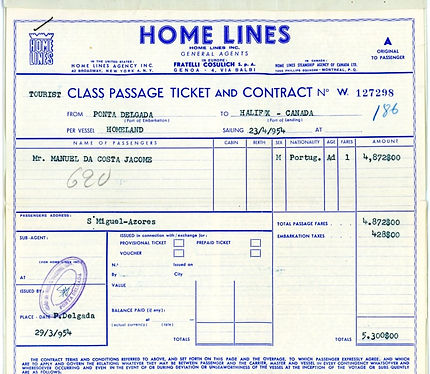

In 1954, my father's one way boat ticket from São Miguel to Halifax cost 5,300 escudos or $176 Canadian. The Canadian dollar was worth 29-30 escudos at the time. For him, and the majority of Azoreans, this represented the earnings of some 400 to 500 days of work. Camponeses or rural

workers, who made up the vast majority of the local workforce, earned between 10 and 15 escudos per day in São Miguel. This is what my father told me and what Afonso Maria Tavares, a pioneer from 1953, confirmed to me a few years ago. In his book, he mentions that a man who worked for him earned 13 escudos in 1952. A few years before, in 1947, his father paid his farm workers 4 escudos a day. Manuel Melo, who immigrated to Canada in June 1957, also confirms the camponês revenue level at the time. He says, in an interview reported in the Small Stories, Great People book, he earned $2.55 in its first day of work in Canada and that it represented a week pay in São Miguel. He had worked 3 hours. For the Micaelense rural worker, saving enough to pay for the travel ticket and other expenses with such low income was almost impossible.

Furthermore, the vast majority of camponeses would only work 92 per year on average following a study made by Pedro Cymbron, Deputy and President of the Ponta Delgada District. The study covered 30,400 local rural workers. He concluded that some 2,800,000 days of work were available per year to those farm workers in São Miguel. Each worker could then expect to work an average of 92 days per year. Only 15 % of camponeses had a guaranteed salary, meaning they will work the full year. (2)

The 5,300 escudos therefore represented 400 to 500 days of work. Total expenses for the trip including the one-way ticket averaged 11,000 escudos, a sum that represents income from some 800 to 1,000 days of work. We are therefore talking about 8 to 10 years of work to pay for travel and other expenses related to the average Azorean immigrating to Canada. Not to mention that you have to eat and raise your family during all those years.

The boat ticket to Canada cost a lifetime's work so to speak. Few had the money required. They had to borrow from relatives and friends. The banks were not lending. They were afraid of never seeing their money again. According to Gil Andrade and many others, it was said that emigrants could be killed by Indians in Canada. Obviously with this kind of investment, very few did think about a return ticket, at least in the short term.

The Iconic Homeland

The Homeland is certainly the most emblematic ship of the 1950s first wave of Azorean emigration to Canada. It carried a total of 780 Azoreans on March 22 and April 23, 1954. The ship has a long and rich history. It was built by Alex Stephen & Sons of Belfast for the Allan Line which launched it on December 22, 1904 under the name of Virginian. Technologically speaking, it stands out with a few innovations including its turbine propulsion system and a three propellers configuration. These innovations certainly provided the ship unique agility and speed, but it also inherited an instability that will never be corrected.

Actress Greta Garbo and Swedish Filmmaker Mauritz Stiller aboard the Drottningholm, August 17,1925. (thegreatoceanliners.com)

The Homeland became the first vessel equipped with steam turbines to be chartered in the North Atlantic. In April, it made his first trip on the Liverpool St John, New Brunswick line. Subsequently it was dedicated to the Liverpool - Montreal line. It was an enormous tragedy indeed, and Canadian Pacific quickly needed another ship to fill the gap of the lost Empress of Ireland. For this purpose, the Virginian was chartered by Canadian Pacific to serve on their Liverpool-Montreal run. The Virginian made a few trips on this run, but the service was soon interrupted by the outbreak of World.

During World War I, the Virginian was used by England to transport troops and later as an armed merchant ship. In 1917, the Canadian Pacific Railroad bought the Allan Lines and thereby the Virginian This service continued through the conflict, and the Virginian seemed to live through it unscathed. Yet in the dying days of the Great War, the ship was torpedoed and started to go down. In order to save it, the Virginian’s captain managed to beach the ship on the coast of Ireland. It was then sold by the company to the Swedish American Line in 1920 and renamed Drottningholm (photo above). The ship was thereof dedicated to the transport of emigrants. Swedish American has done extensive work on the ship. Its first class was already of a good standard. But the lower levels, where all the poor are crammed together, had to be renovated. Swedish American also opted for less efficient but more economical engines. The travel industry was ticking up after the war. Adjustments were necessary to take advantage of the new customers. The ship made its first voyage to the United States on August 17, 1925. Famous Swedish actress Greta Garbo and film producer Mauritz Stiller were on board.

In 1937, the Drottningholm was repainted in white. During World War II, it served as a hospital ship by the Red Cross. In 1948 it was acquired by Home Lines which renamed it Brasil and assigned it to the Genoa-South America route. In 1950, Home Lines moved it on its Genoa-Naples-Halifax-New-York route. In 1951, she renamed the 1,700 passengers liner, Homeland. The iconic ship was sold for scrap in 1955. The Homeland was then, with nearly 50 years in operation, the oldest transatlantic in service. (3)

References

-

Carlos Cordeira et Artur Madeira, Portuguese Reviews, Vol. 12, No 2. page 186

-

Carlos Cordeira et Artur Madeira, Portuguese Reviews, Vol. 12, No 2, page 179

* Audio recording made by Marc-André Delorme, who interviewed Azorean pioneer, Gil Andrade,

part of the Cliniques de la mémoire project.

About the author

Born in São Miguel and living in Montreal since 1958, I published a book in 2018 about Azorean immigration to Canada in the 1950s. “De uma ilha para outra” was published in Portuguese and French. The book and an exhibition that accompanies it were presented in Montreal, São Miguel, Toronto and Boston. The book is sold in Montreal, Toronto and São Miguel, and through my Website. I continue to publish information and stories relating to the first big wave of Azorean and Portuguese immigration to Canada in the 1950s through my Website jljacome.com and my Facebook page D’une île à l’autre.